FASB’s New Rules for Purchased Loans: A Simple Guide to the Big Changes

Have you ever looked at a complex accounting rule and just thought, “That… doesn’t seem to make any sense”? As someone who follows financial reporting, I’ve had that feeling more than once. Well, for years, there’s been a particularly “weird and counterintuitive” rule on the books about how companies account for loans they *buy* from other institutions.

The good news? The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) heard the complaints and has finally issued a new update to simplify things and, honestly, just make it more logical. This change fixes a major flaw we all call the “double count” problem. So, let’s dive into what was wrong, how FASB fixed it, and why this change is a huge win for common sense. 😊

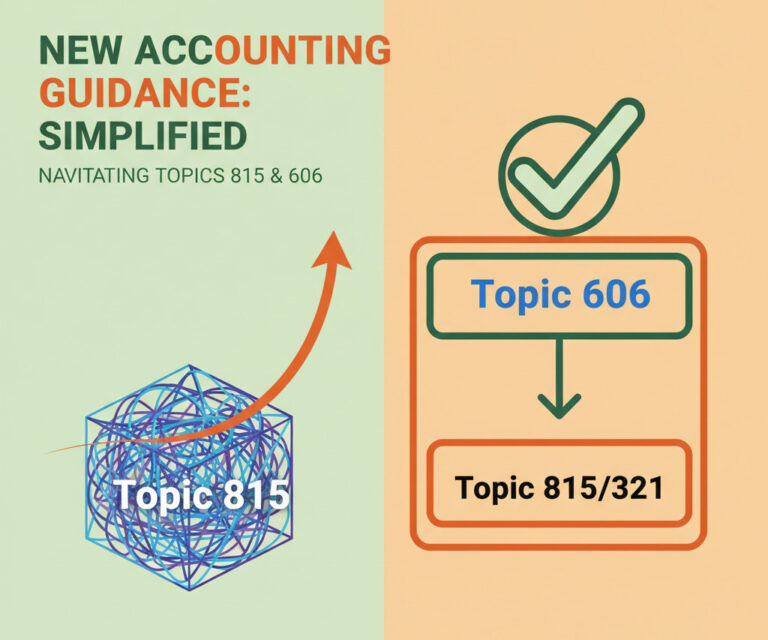

The Old Way: A Confusing “Fork in the Road” 🤔

To understand why the new rule is so great, we first have to appreciate how messy the old system was. Every single time a company purchased a loan (or a portfolio of loans), accountants were forced to a “fork in the road.” They had to decide which of two completely different accounting paths to follow. This choice wasn’t just annoying; it created a ton of extra work and led to some truly bizarre financial reporting outcomes.

Here were the two paths:

- Path 1: PCD (Purchased with Credit Deterioration) Loans. These were the “shaky” loans. Think of loans that, at the time of purchase, already showed signs that the borrower might not pay it all back. For these, the accounting was sensible. You used a “gross-up approach.” In simple terms, you’d bake the expected losses right into the loan’s value from the start. No immediate, scary hit to your profits. It was logical.

- Path 2: Non-PCD Loans. These were the “good” loans—the perfectly healthy ones. And here’s where things got weird. The accounting for these was the *total opposite* of the PCD loans. If you bought a perfectly healthy loan, the old rule required you to immediately record an expense for any expected future credit losses. This meant taking a direct hit to your company’s earnings on Day 1, just for buying a high-quality asset!

You read that right. The old standard essentially penalized companies, at least on paper, for buying healthy loans, while the accounting for “bad” loans was more straightforward. It was this inconsistency that drove investors and companies nuts… and for a very good reason.

The “Double Count” Problem: Why the Old Rule Was Flawed ⚠️

So, what’s the big deal with taking a Day 1 expense? This is where we get to the core of the flaw, a logic-bomb that stakeholders called the “double count” problem.

Think about it. When you buy *anything* on the open market, its price is set by “fair value.” If you’re buying a loan, the price you pay (its fair value) *already reflects the risk*. You’re not going to pay 100 cents on the dollar for a loan that has even a small chance of default. The seller won’t get the full par value. That risk is “priced in” as a discount.

Stakeholders rightly pointed out that recording a *separate* expense for those exact same expected losses was, in effect, accounting for the same loss twice. You “paid” for the loss once via the price discount, and then you were “charged” for it *again* as an expense on your income statement.

This concept is so important, so here’s a simple analogy from the video that explains it perfectly.

- Imagine you go to a store and find a sweater you like, but it has a small, visible hole in it.

- You take it to the register, and the cashier gives you a 20% discount *because* of the hole. You happily pay the discounted price.

- The old accounting rule (Path 2) was the equivalent of you going home, and then, on top of the discount you already received, writing down a *separate* 20% “hole expense” in your personal budget.

This “double count” wasn’t just a theoretical annoyance. It was a real mess. It made company financials more complex, it made it incredibly difficult for investors to compare one bank’s loan portfolio to another, and it distorted the true financial picture, sometimes making a loan’s returns look artificially high later on. It was clear a change was needed.

FASB’s Solution: The “Gross-Up” Approach for More Loans 💡

And guess what? FASB listened! They received the feedback from investors, accountants, and banks, and they agreed. The “double count” problem was real, and it needed to be fixed.

Their solution is elegant and, frankly, rooted in common sense. The new update doesn’t reinvent the wheel; it simply takes the logical method that was *already* being used for PCD loans (Path 1) and expands its use. This is the “Gross-Up Approach.”

So what is this magical “gross-up” method? It’s actually very simple. Instead of booking a Day 1 loss, you use the expected losses to establish the baseline *value* of the asset. It works like this:

📝 The Gross-Up Approach Formula

Loan’s Initial Amortized Cost = Purchase Price + Allowance for Expected Credit Losses

By adding the allowance *to* the purchase price, you “gross up” the asset’s book value to the total amount you expect to collect. The “allowance” (the part you might lose) is recorded on the balance sheet as a contra-asset, but crucially, **there is no Day 1 hit to the income statement.**

This approach completely avoids that weird, illogical Day 1 expense for losses that were *already* baked into the purchase price. It’s a huge win for simplicity and logical accounting. But to make this work, FASB had to create a new category…

A New Category: What Are “Purchased Seasoned Loans”? 📊

Under the old rules, you basically had two buckets: “Bad” (PCD) and “Good” (Non-PCD). The “Bad” loans got the good (gross-up) accounting, and the “Good” loans got the bad (Day 1 expense) accounting. How ironic!

To fix this, FASB’s update introduces a new “middle” category that is eligible for the sensible gross-up treatment. This new category is called “Purchased Seasoned Loans” (PSLs).

So, what exactly is a “Purchased Seasoned Loan”? It’s a loan that isn’t a “bad” PCD loan, but also isn’t brand-new. The official criteria are quite specific, but they’re designed to capture these “in-between” loans. Here’s a simple breakdown:

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Loan Type | Can be pretty much any type of loan or debt security. |

| Exception | The video notes that credit cards are excluded from this definition. |

| Initial Check | Must be a Non-PCD loan. (i.e., it didn’t have significant credit deterioration when you bought it). |

| The “Seasoned” Test (Must meet ONE) |

|

That last point is the big one. The 90-day “seasoning” period is the key. It allows FASB to separate loans that are truly “seasoned” from brand-new ones that are just changing hands. If a loan meets these tests, it’s a PSL and qualifies for the gross-up approach.

The New 4-Step Decision Process 🧮

The best part of this change is how it cleans up the decision-making process for accountants. The confusing “fork in the road” is now a much more logical, streamlined path.

Here’s the new, simpler decision process:

- Step 1: Assess. When you buy a loan, first assess it for significant credit deterioration. If it has any? It’s a PCD loan. Your process ends here. You use the Gross-Up Approach (just like before).

- Step 2: Check. If the loan is healthy (Non-PCD), you now have a second step: Check if it meets the new “seasoned” criteria (Is it >90 days old? Was it part of a business combination? etc.).

- Step 3: Identify. If it *does* meet those criteria, you identify it as a “Purchased Seasoned Loan” (PSL).

- Step 4: Apply. For all PSLs, you apply the Gross-Up Approach—the same sensible method used for PCD loans.

What about healthy loans that *aren’t* seasoned (e.g., a loan you buy just 10 days after it was created)? Those will still fall into the old Non-PCD bucket and may have a Day 1 expense. But this new process successfully funnels *so many more* loans (PCDs *and* PSLs) down a single, consistent, and logical accounting path. It’s a massive improvement.

Why This Update Matters for Everyone 👩💼👨💻

Okay, so we’ve covered the mechanics. But let’s pull back for a second. Why does this accounting change *actually* matter in the real world? Why should you, whether you’re an investor, an accountant, or just curious about finance, care about this?

The benefits are pretty huge:

- Massively Improved Comparability. This is the big one for investors. Under the old rules, you couldn’t easily compare two banks. One might have a portfolio of “healthy” loans (and the big Day 1 expense), while another had “shaky” PCD loans (and no Day 1 expense). It was apples-to-oranges. Now, you can actually look at two companies’ books and know you’re comparing them on a more level playing field.

- A Simpler Life for Accountants. Let’s be real: less complexity is always a good thing. This rule removes a major point of confusion and inconsistency, making financial reporting more straightforward and less of a headache.

- Financials Finally Reflect Reality. The new rule just *makes more sense*. It aligns the accounting treatment with the economic reality of the transaction. The “double count” is gone, and the balance sheet now more accurately shows what’s going on.

- It Finally Fixes the Frustrating “Double Count.” This is the most satisfying part. A logical flaw was identified, the industry spoke up, and the standard-setter fixed it. It’s a win for logical consistency.

When Does This Take Effect? 🗓️

This isn’t happening tomorrow, but it’s on the horizon. The new standard officially takes effect for fiscal years that begin after December 15, 2026.

However—and this is a key “however”—FASB is allowing companies to adopt these new rules early! So you might start seeing this new, simpler accounting pop up in financial reports sooner rather than later. Keep an eye out for it!

Because this update is seen as a “simplification” and an improvement, companies have the option to adopt it early. This is great news, as it means we could see the benefits of this change (like better comparability) start to roll in well before the 2026 deadline.

FASB’s New Loan Rules: Key Summary

Conclusion: A Win for Common Sense 📝

This whole update is a fantastic example of the industry pointing out a flaw and the standard-setters listening. It’s a move away from complexity for complexity’s sake and toward financial reporting that actually reflects what’s happening. It just… *makes sense*.

It really makes you wonder: Will this successful push for simplicity set a new trend? Could we see more of this common-sense approach to simplifying other complex parts of financial reporting? We can only hope!

What are your thoughts on this change? As an accountant, are you relieved? As an investor, does this make you more confident in financial statements? Let me know in the comments below! 😊